Bill Courtney made his mark in Memphis as the volunteer football coach of the Manassas Tigers and a successful businessman. Now, he’s aiming to reach a much larger audience with the launch of a new podcast called “An Army of Normal Folks.”

Courtney’s inspirational message to an underrated high school football team in North Memphis became the subject of the Oscar-winning documentary “Undefeated.” He followed that with a book, “Against the Grain: A Coach’s Wisdom on Character, Faith, Family, and Love.”

On today’s edition of “The Daily Signal Podcast,” Courtney explains why he decided to take action in his local community—and why he’s encouraging you to do the same. His new podcast features stories of normal people who are doing their part to change lives and our country.

Listen to the full interview or read a lightly edited transcript below.

Rob Bluey: Those who have watched the documentary “Undefeated” know a little about your own personal story, but for those who haven’t, let’s begin with this question: How did you end up in one of Memphis’ troubled neighborhoods coaching a football team that was considered one of the worst in the state?

Bill Courtney: I mean, we don’t have four hours to go into the whole story, but basically, I grew up in Memphis. Dad left home when I was young, mom was married and divorced five times, and I had a couple of grandfathers that were good guys that had an impact on my life.

But candidly, the most impactful people in my life were my football coaches coming up. And had I not had good men in my life as football coaches, I’m not sure exactly the track my life would’ve taken.

So I graduated from Ole Miss and all I wanted to do was coach football. The problem is I married my wife and we had four kids in four years and $17,000 a year coaching football, no insurance, wasn’t getting it done.

And so I had to leave football coaching as a profession, ended up starting a lumber business. But in the state of Tennessee, you can be what’s called a non-faculty certified football coach if you go through a bunch of classes and get all the certification. And there’s a few of those guys in the state of Tennessee, I’m one.

So while I was starting my business and transitioning away from football as a profession, I continued to stay in it as a passion and continued to coach and started a business with almost no money and bought some property in the most dilapidated, crappy part of Memphis.

And Manassas High School was less than a mile from where I started my business. And through some introductions, I was asked if I would be interested in coaching at Manassas.

Candidly, how I ended up there is I started a business near it and it was convenient, but I didn’t understand what I was getting into when I showed up. And there were 17 kids on the team and they’d won four games in 10 years. So it was a turnaround project. And then the movie that you talk about is our last year there, which was seven years later.

Bluey: It’s truly remarkable. I highly recommend the film. Could you paint a picture for us what it’s like to be a student at Manassas High School in North Memphis? What’s the profile of the types of students who were on your football team?

Courtney: There are three communities that largely support the student body at Manassas. One is called Smokey City, the other is New Chicago, and the other is Greenlaw. … I think the demographics are, I think it’s a third- or fourth-poor ZIP code in the United States. In seven years there was one white student at Manassas and the rest were all African American.

Some of the demographics are only 0.3% of the people from those neighborhoods have a college degree. Only 51% have an operating vehicle. Unemployment rate is around 43%. An 18-year-old male is three times more likely to be incarcerated or dead by his 21st birthday than he is to have a job.

So I don’t want to sensationalize it. Everything I’m saying to you right now are facts, but it is the type of community that movies and media and the press do sensationalize.

It is the poorest of the poor, most disenfranchised, most underserved, food desert, dilapidated, horrific circumstance that—I mean, honestly, I travel all over the world with my business. We do business in 42 different countries and I travel to many Third World countries, doing business in Asia and across Central, South America and Europe. And I will tell you, even in South Africa, there aren’t many neighborhoods worse than those that surround Manassas.

Bluey: How did the players react to your arrival and the discipline and the character-building that you brought and required of them?

Courtney: With curiosity at first because most of it was foreign, but I had a hook and the hook was football.

And if you wanted to play football and you wanted to be part of a program that I was on—pulled into a winner by bringing in coaches, new equipment, uniforms, giving the kids a kind of level playing field to just have an opportunity to compete and to be part of something that was first class, which very little in their orbit was first class.

If you want to be part of that, I’ll have to adhere to these tenants: character, commitment, integrity, teamwork, all of the core values that you hope you learn when playing football that lasts you long after the playing days are over.

And candidly, it was tough. I had kids that were being asked to subscribe to notions and behave in a way that was not necessarily part of their world, but I don’t want to sensationalize it. I’m going to tell you something from the day I showed up, first day, it was, “Yes or no, sir.”

The principal at that school worked hard to keep the hallways clean and the kids where they were supposed to be. I don’t want you to picture some sensationalized movie that looks like kids hanging around and smoking weed in the hallway or in the parking lot or a bunch of disrespectful teenagers. It wasn’t that at all.

They were actually really respectful kids that just wanted to be part of something that was good. And a lot of the tenants and a lot of the rules that I held them accountable to, they just [were] foreign to them. They’d never been held accountable to those rules.

And so it was painful to create a culture that won in football, but not only in football, in life. And it didn’t happen in one month or even one season. It took a couple of years to really, actually, three years to really make that transition happen.

But we went from a team of 17 kids that won four games in 10 years to a team of 75 kids who were 18 wins and two losses their last two years. And that turnaround is a direct result of those kids deciding they were going to buy in and conduct themselves in a little bit of a different way to try to find success not only on the football field but in their lives.

Bluey: What kept you going back year after year?

Courtney: If I’m walking down the street, you’re going to see a 54-year-old white dude who owns a $90 million lumber company and drives in a nice car, lives in a nice house, has been married to the same woman, who I will stay married to for the rest of my life, that I am in love with today as much as I was the day I met her. I have four grown children, all gainfully employed, doing well.

So when you see me, you’re going to sum me up as a probably upper, maybe even upper-middle, maybe even upper-class white dude living in a nice house. And you’re going to think you know me, you don’t. That’s not my reality. That’s not where I come from.

I came from dysfunction. My mom’s fourth husband shot at me down a hallway one night. I had to dive out a window to save myself. I don’t come from what you think you would see when you see me.

And the truth is, as a child, as a kid, and as an adolescent, I identified with the kids at Manassas a lot more readily than I identified with even my own children.

So what kept me going back was that I knew that with some love and some dedication and some commitment and some accountability, that these kids had an opportunity to do something with their lives.

And I didn’t see it as a nice thing to do. I saw it more of as a calling and more as an opportunity to give back in a way that men gave to me when I was their age and struggling with my own identity and my own in insecurities and my own fears and my own dreams.

So what kept me going back was, every once in a while, one of these kids would do something just amazing and cross over a new step that I didn’t know that maybe they could cross over. And frankly, the kids inspired me to keep coming back. And to this day, it’s one of the most rewarding experiences of my life because I learned so much as a result of my time with the players at Manassas.

Bluey: That is an incredible story and an inspiration. I hope listeners of this show and others follow a similar path. As we just heard from you, you’re really one of the normal folks. How did the experience of being the football coach and writing the book “Against the Grain” lead you to this idea for the podcast?

Courtney: Honestly, it’s like everything else in my life. I’m not really sure how it happens, but it does.

Listen, after the Academy Awards, I thought I had my 10 minutes in fame, and Lisa, my wife, and I enjoyed it. The kids enjoyed it. We had a big time. And I went back to Memphis and planned on running my lumber company, coaching football, and whatever.

And then people started calling me and wanting to do speeches. And so I started doing keynote speeches and still doing them for a variety of venues, stuff like the Olympics, for goodness sakes, and Nike and Frito Lay and all these cool places. And it was awesome. And it gave me a platform to talk about stuff that I think we need to talk about, like politics, like race, like political belief and creed and faith.

I think it’s high time that we put aside the fear of how somebody’s going to categorize you because of your opinion and start having real open, candid conversations about the stuff that matters, but just do it in a civil, nonthreatening way.

And this movie showed me as this guy who came from interesting circumstances, coached football and ran a lumber company, and it gave me this platform to say some things that I think need to be said and give people an opportunity to think about things a little differently.

Then from that came, “You need to write a book about all this stuff.” So then I wrote a book, which led to more speeches and more interviews. …

We didn’t produce a movie. Some goofy guys that were 29 years old showed up from Hollywood and followed us around for nine months and made a movie that we thought nobody would see. And it ended up winning an Academy Award. It just happened.

And so in one of my interviews, I was interviewed by Alex Cortes, who is now the producer of “An Army of Normal Folks.” And he was asking me a bunch of questions like you’re asking me now. And I was as candid and real as I could be, like I am with you now.

One of the things I said was that we all have streets or areas or even viaducts that when you’re driving around our communities that you just don’t want your car to break down, you don’t want to have a flat tire, especially in every major city. DC has them, Memphis has them, everybody has them.

And when you pass by those areas and you look over and you see the disenfranchisement and the loss and the despair, you do think to yourself, “Gosh, that is terrible. Somebody has to do something about that one day,” as if that sentiment matters. Sentiment doesn’t mean anything. It doesn’t move the yardstick and it helps nobody. In fact, it’s basically hypocritical to even look down into a space like that and say that from your $50,000 car.

So my suggestion is maybe you tilt that rearview mirror about 30 degrees and look yourself in the face and say, “Hey, maybe I ought to do something about that.”

I think government has proven woefully inadequate. I think a lot of well-intentioned programs that may be decades old have gotten to be almost paternalistic and keep some of the most disadvantaged among us in that disadvantaged state.

And I’m sick of fancy people on CNN and Fox using big words that nobody really ever uses in conversations and nobody really understands and as if they’re going to change anything.

I think we have dysfunction in culture, society, and our political discourse, and meanwhile, there’s need everywhere and it surrounds us daily. And I just think it’s going to take an army of normal folks. I just think it’s going to take average folks seeing a place of need in their communities and filling it.

And I do believe that, and I said that to Alex. And so Alex came back to me about six, seven months later and said, “I can’t quit thinking about that conversation. I want to launch a podcast called ‘An Army of Normal Folks’ with two objectives. One, to tell the stories of normal folks doing extraordinary things across our country that change lives. And two, to have people join the Army of Normal Folks to join in a movement that says, ‘This is our country, this is our culture, this is our society.'”

The power brokers, the few power brokers that are out there that are dividing us with media and politics cannot combat an army of normal folks just saying, “You know what? I can help in my world, in my society.”

So we started doing interviews. We’ve canned 20 so far in the podcast released today. And we are telling the stories of extraordinary people who have done extraordinary things.

And they are black and white, and Christian and non-Christian, and Left and Right, and moderate and center, and male and female, and from all walks of life. And from it, I’ve learned nobody has a monopoly on philanthropy or kindness. And it is phenomenal, the amazing things that go on in our world and our country every single day that we never hear about and we never focus on.

And I want to grow an army of normal folks, a movement of people who celebrate each other despite their differences and who come together around kindness and decency and civility and celebrate one another’s differences instead of villainize each other over them.

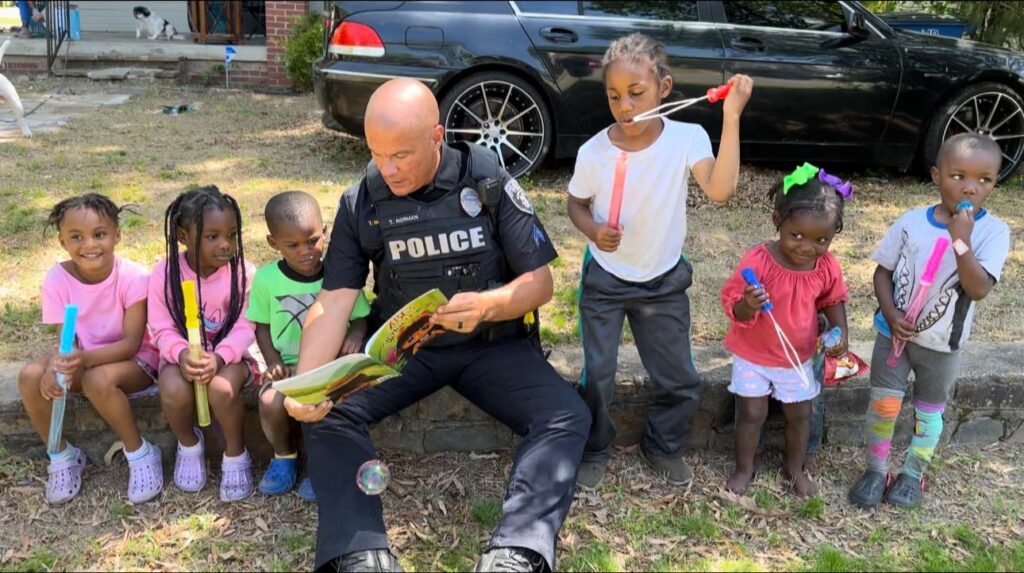

Bluey: You launched this week with the story of Police Officer Tommy Norman. Your interview with him is available now. Who is he and why did you decide to lead with him?

Courtney: I got a crush on him. I got a deep crush on this guy when I met him, really. I mean, this guy is from North Little Rock, Arkansas. One of nine children. Grew up in a house with one bathroom. He said his six sisters would choke them out every morning with Aqua Net.

I mean, his mom was a stay-at-home mom and his dad was a contractor. I mean, we’re talking blue collar, probably lower end financially, trying to feed all those people. And he became a cop.

The reason he became a cop is because his uncle was the chief of police at Hot Springs Village, south of Little Rock, about an hour and a half. And he respected his uncle and the way his uncle looked and his crisp uniform and the way his patent leather gun belt sounded and squeaked when he got up. And he revered the guy and he became a cop.

He said that he knew two things about cops: They pulled people over and wrote tickets and they arrested folks. And he knew as a cop, he would have to do that, but he also thought a cop could do something else, which is serve, literally serve.

And in North Little Rock, it’s an interesting place. It’s only 70,000 to 90,000 people, but there’s upper class, middle class, and then there are the projects in North Little Rock. And he works where the poverty is.

And this cat parks his car and walks his beat, old school, and his goal is threefold: to get invited into somebody’s front yard, to then get invited to that person’s front porch, and then from the porch get invited to their dinner table to have breakfast, lunch, or dinner with them. That is his goal.

Everywhere he goes, he gets the phone numbers of the people that are on his beat and on his off day, he calls them and checks on them, makes sure they’re doing OK.

He’s been invited to birthday parties, he’s been invited to weddings, he’s been invited to dinners, he’s invited to kids games. He’s routinely seen out on the basketball court in these areas playing basketball with his gun belt on. He’s routinely seen break dancing in the streets. He’s spoken at funerals. He’s also a cop and he’s arrested people that broke the law, including murderers, but he does it with dignity.

And his favorite basketball player was Michael Jordan. He even shaves his head today because Michael Jordan shaves his head.

And here’s this guy, Tommy Norman from Little Rock, who decided, “I’m going to police differently and serve.” Just one guy, not the captain of the police force or anything. And he’s now considered the Michael Jordan of community policing, and he’s showing a different way to police and to break down the bounds of racial fear about cops.

At the same time, he had his own personal struggles and he lost his daughter to a drug overdose during the middle of all this. And he had heart problems and he struggled. And despite his own personal struggles, he continues to be the shining light in North Little Rock as an officer.

And our current social discourse says that people in poverty, largely in African American neighborhoods, are supposed to fear the police, especially white ones. And he has destroyed that narrative by simply getting out of his car and having conversations with people and showing he cares.

And that is just our first story. We have stories of all kinds of other stuff, but because he was so inspiring to me and because—I mean, he’s got this crazy following. He’s got 2 million followers on Facebook from just being a good cop, a good person. I mean, what a novel idea. Be a good human being and serve those around you.

And there could not be a better opening to what we’re talking about when we’re talking about an army of normal folks seeing need in their communities and filling it and changing our culture. And I just think he’s the poster child for it.

So he’s first, and then next week we will talk about a—I’m not going to spill the beans completely, but we’ll talk about a young woman who struggled with addiction in her family and she had some issues she was dealing with and in the middle of all of it did something that has turned around the fortunes of thousands of homeless people by teaching them to run. An incredible story. But that’s for next week.

Bluey: It’s truly fantastic that you’re giving these people a voice and you’ve hinted that this could be bigger than just a podcast. What do you mean by seeing it develop into a movement of normal folks?

Courtney: If you go to normalfolks.us, you can sign up to just be a part of the army. Now, that’s a little hokey and a little goofy and I get it, but I mean it.

And when you sign up, you’ll get information from “An Army of Normal Folks” about when the podcasts come out and what’s going on. You’ll be able to see the pictures of the people that we interview. And little by little, I hope to grow those numbers so that as we grow those numbers, we can use that community of people to start making some statements.

I know it’s a pipe dream—maybe it’s not a pipe dream. I know it’s a dream. But can you fathom a group of tens and hundreds of thousands of people who say, “Yeah, I’m a normal person and I like good things to happen in my communities”?

And some are Democrats and some are Republicans and some are moderates, and some are black and some are white, and some are Asian and some are Hispanic, and some are Christians and some are Jewish and some are agnostic, some are Muslims and some are Hindus, and some don’t care about any of that stuff.

But they’ve all found something that they can agree about and that they can get behind and that they can subscribe to, which is, “Let’s find places of need in our communities and fill it.”

Can you imagine? We’re always talking about, how do we fix what divides us? In my mind, we celebrate our differences and we work together to create a better society.

And it’s a podcast, and hopefully it’ll be redemptive and interesting, and you will laugh and you will think and you’ll be entertained. And I want you to listen.

But hopefully, after listening and being entertained and laughed and hearing the stories, you’re also motivated to become part of something bigger than yourself that maybe can change some of what we have been taught this last decade and a half, to think about one another because of the particular group we happen to be from, which is completely destructive to our society.

Bluey: Congratulations for getting picked up on iHeart. How can people listen?

Courtney: Go to iHeart and download it. You can go to Spotify, you can go to Google, you can go to Apple, you can go to normalfolks.us and download it. Just basically, wherever you listen to podcasts, you can find us.

And again, my hope is that people listen, people like it. And I have learned in pretty short order that podcasts, they do well as people share them and suggest them. And so my goal is to get people to listen and join up and enjoy it, and then share it and share it on social. Share it with your friends, get people to listen. And much like our conversation today, which I really appreciate, just trying to get as many people’s ears to understand this thing’s out there.

Give it a shot and I bet if you listen, you’ll come back.

Bluey: A good rating and a good review as well. That’s always helpful, right?

Courtney: Rate it, review it, share it. Gosh, I’m starting to get sick of myself now. I’m starting to feel like a commercial. But honestly, that’s what you got to do. Rate it, review it, share it. Listen, join, and let’s have some fun. Let’s hear some redemptive stories. Let’s be inspired and maybe as a group we can do something special.

Bluey: Coach Bill Courtney, the podcast is called “An Army of Normal Folks.” Thanks so much for being a guest on “The Daily Signal Podcast.”

Courtney: Thanks for having me. Really appreciate it.

Have an opinion about this article? To sound off, please email letters@DailySignal.com, and we’ll consider publishing your edited remarks in our regular “We Hear You” feature. Remember to include the URL or headline of the article plus your name and town and/or state.

The post Football Coach Builds ‘An Army of Normal Folks’ to Solve America’s Problems appeared first on The Daily Signal.

0 Commentaires